On Monday afternoon, the University of California, Berkeley thrummed with the sights and sounds of protest reverberating from picket lines along Bancroft Way.

A huge sign reading “END RENT BURDEN” stretched across the worn bronze arch of Sather Gate. Nearby, a duo kneeled on the concrete of Sproul Plaza, scribbling messages in bright streaks of chalk. Others painted banners to hang on facades and fences; one already waved from the side of the student union building declaring “NO COST OF LIVING ADJUSTMENT, NO GRADES.”

Eventually, a group of several dozen people assembled into a loose circle in the center of the plaza. They began marching again, signs aloft, as graduate student researcher Greg Ottino yelled into a bullhorn.

“What do we want?” Ottino asked.

“Fair contracts!” the marchers shouted back.

“When do we want them?”

“Now!”

“If we don’t get it?”

“Shut it down!”

This moment was a long time coming for Henry Liu, a graduate student researcher for the physics department. Liu, 24, gestured to the picket line and told me that the cost of living in the Bay Area, coupled with a lack of consistent support from the university, had a widespread negative impact on those tasked with day-to-day research and teaching on campus.

“I signed my union card last fall, but I really got more involved in organizing beginning this January. I just started talking to more and more of my coworkers, and realized that this isn’t a problem for me as an individual. It’s a systemic problem across the UC,” Liu said. “Rent burden is an insurmountable challenge without change. Inflation was at more than 8 percent this year. Our wages haven’t grown at all.”

Monday was the first day that an estimated 48,000 people began striking across 10 UC campuses, in what organizers described as the largest academic strike in U.S. history. It comprises four groups represented by United Auto Workers, one of the biggest unions in America: post-doctoral scholars, graduate student researchers, academic researchers and student employees (such as teaching assistants and tutors).

It is a noteworthy chapter in a wave of strikes unfolding across America, as well as a landmark effort to change a national history of academic institutions using students and postdoctorates as cheap and replaceable labor.

The union authorized the strike after the UAW filed some two-dozen unfair labor practice complaints against the university and concluded that officials were no longer bargaining in good faith. As predicted, the strike is causing major disruptions on campus, slowing research, grading, and office hours. Some faculty members canceled their classes altogether or moved them to online-only sessions in solidarity with the strikers.

There is no planned end date to the strike. A number of strikers indicated that they’re prepared for the long haul, including Kai Yui Samuel Chan, 30, who is a graduate student instructor in the Political Science program at Berkeley.

“The UC wants to do what is convenient for the institution. It feels like some of us are just invisible to them. They often resort to window-dressing to resolve issues of inequity, instead of addressing material conditions meaningfully,” Chan said. “It seems they’re reluctant to commit themselves to anything that they can’t walk back in the future.”

Today’s strike isn’t entirely without precedent. Three years ago, graduate student assistants at UC Santa Cruz embarked on an audacious action: despite no authorization or support from their union (UAW Local 2865), a group of nearly 80 launched a wildcat strike, withholding grades for the semester and demanding that the university increase their monthly pay by $1,412. They were summarily fired by the university, and while many were ultimately reinstated, this setback served as a radical wake-up call to increase representation within the union, coordinate action across UC schools, and prepare for a bigger fight ahead.

As with everything else, the pressures of the pandemic have only sharpened the need for change, said Evan Holloway, a clinical psychology PhD at UCSF.

“I’ve seen a lot of hope, people being radicalized, and the clarity of so many inequities becoming impossible to ignore during the pandemic. More and more people are asking the UC system to get their shit together. They’re coming together to suggest that there has to be a different way,” Holloway, 36, said. “It’s been really hard to organize during a pandemic. But it’s a very historic time.”

The seminal moment arrived in 2021, when academic workers at Berkeley and UC San Francisco began signing union authorization cards in order to be recognized by the university. While the UC system voluntarily did so, breakdowns in contract negotiations since have led to a firm set of demands, including $54,000 a year for graduate students, $70,000 for post-doc workers, increased childcare benefits, and the cutting of a $15,000 tuition fee on international academic workers.

The UAW’s member surveys w found that 92% of graduate workers and 61% of postdoc scholars are rent-burdened, defined as paying more than 30% of their income on housing. UC officials have thus far offered a salary scale increase that ranges from 4-10% in the first year (dependent on the role), with small raises in following years and a suite of increased benefits. It’s an offer that falls well short of union expectations for a raise big enough to end the rent burden outright.

On Monday night, university officials called for a “neutral private mediator” in the hopes of restarting the stalled talks. But on Tuesday the picket lines were back in full force, including at UCSF’s campus in Mission Bay. That first long, uncertain day of action turned out to be a welcome shock to the system, Maura McDonagh told me, energizing picketers and inspiring curiosity from students.

McDonagh, 26, works as a graduate student researcher studying multiple sclerosis at UCSF. She traces the “spark behind the flame” of the strike to last May, when a group of academic workers marched to the office of the UC president in Downtown Oakland and handed in thousands of union authorization cards to form what is now Student Researchers United.

Like Liu, McDonagh says she was motivated by the many one-on-one conversations she had with other academic workers in 2021. Those talks painted a broad picture of underpaid and overworked people with little recourse within the system. It also proved to her that she wasn’t alone in feeling pinched.

“I find it infuriating that the UC believes that, when they propose their compensation demands, student researchers are seen as only working part-time. I have spent 60 hours a week in my lab. I’ve gotten on BART at five, six in the morning to come to campus and wean a mouse cage,” she told me. “To do all that and have the university tell me that our cost of living is something that can’t really consider … If we can’t afford to live while doing integral work for the university’s benefit, what does that say?”

By all accounts, this week’s strike has been a historic moment for pushing wage parity in higher education, an industry that provides disproportional benefits to full-time faculty and administrators at the expense of the workers that make a world-class university possible.

The strike offers a crucial time for reflection, too: the long-held mythology around graduate student research and post-doc work promised that sacrificing time and money would pay off in the future, especially if one labored under a mentor with influence and connections in their field. In reality, the landscape for careers in academia appears more tenuous and shaky than ever, with a notable lack of tenured positions for post-docs to vie for. Meanwhile, a growing number of people in graduate programs have concerns that their degree training has failed to prepare them to secure a job in the non-academic market.

“There has been a shift in the labor market, and PhD programs have not changed sufficiently to adapt,” Shweta Ganapati, a policy adviser at the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, told Nature this month. “There’s a reason why they are not optimistic. We can fix this, but we aren’t moving fast enough.”

The gloom is worsened by rising housing costs, which continue to press upon some of the most desirable universities in America. As Chan noted on Monday, the whole point of him leaving Hong Kong to attend Berkeley was to experience a genuine diversity of economic class and perspectives in a public institution. What does it mean if these thousands of graduate and post-doc positions can only be filled by people with enough money and resources to tolerate minimal wages and uncertain futures?

It is an existential concern, especially as the state of California looks to add to the UC’s coffers in the next budget.

The historic nature of the strike hasn’t gone unnoticed outside of California. On Wednesday, part-time faculty members at the New School and Parsons School of Design in New York went on strike, decrying a lack of wage increases despite rising cost of living as well as the salary disparity compared to administrators’ pay.

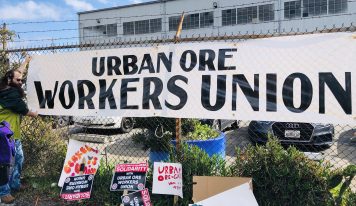

Solidarity efforts in support of the UC strike have also bloomed: The California Labor Federation called for all events on UC campuses to be canceled, and various workers from other trade unions have refused to cross the picket line, halting construction on a much-hyped data and computer science center at Berkeley. UPS drivers drove up to UCSF’s Mission Bay campus to honk their horns and refuse to deliver packages, a public display of solidarity courtesy of the Teamsters Union.

Momentum is building, and the picketers’ resolve is firm. It’s unclear what exactly the strike will win at the negotiating table — but it is already apparent that this UC strike could very well become a flashpoint in the debate about inequality in higher education, and inspire a new generation of labor organizers to rise.

Photos by Eddie Kim