On September 28th, service workers at San Francisco International Airport (SFO) announced a tentative agreement to call off their three-day strike. The strike came after nine months of negotiations with the owners of the airport concessions who failed to produce a contract that was up to the workers’ standards. SFO’s 1,200 service workers, represented by UNITE HERE Local 2, were demanding a pay raise to keep up with inflation and the cost of living in the Bay Area, improved health insurance, and stricter rules around worker retention.

The workers were bargaining with a collective of owners who run businesses at SFO. Despite numerous efforts to apply pressure on the owners, including pressure from local politicians, the negotiations stalled and Local 2 held a strike vote. The strike was approved by 99.7% of the voters.

After three days of picketing at SFO’s terminals, the bargaining team sat down with the owner collective and worked out a new contract that met the workers’ demands. The new contract included a 30% raise over the next two years, increasing the median wage among airport service workers from $17.05 per hour to $22.05 per hour. The contract also included coverage for platinum-level health insurance, clearly defined seniority retention rules, and a one-time bonus of $1,500.

We recently spoke to Tom Kreis, a rank-and-file Local 2 member who helped organize the strike. We asked them how the strike came about, what it was like, and what they hope others learn from their success.

Talk about the time leading up to the strike. How did the negotiations go? What was the feeling among workers at SFO?

We had spent nine months trying to negotiate, and from the beginning, something felt off. Rather than a standard negotiation where you work to meet a middle ground, the owners seemed determined to lower our demands across the board. Local 2, which represents 1,200 workers at SFO, bargains with a group of owners who are bargaining collectively. Some owners don’t participate and are disengaged, others not as much. The airport serves as a separate entity that tries to “keep the peace,” which can play an interesting role.

There’s a rule at the airport where businesses cannot interfere with union organizing. If employees want to organize, the owners have to stay neutral. However, certain new businesses where employees signed pledge cards prevented their employees from unionizing. We made a lot of effort to get assistance from the airport to stop this, but we were unsuccessful.

For example, Terminal 1 reopened and got a lot of new businesses, and we ran into some issues there because the new owners were not familiar with the rules of the airport. Our last strike was in 2014 and it was a similar situation — we had a new terminal with many new owners who didn’t understand how bargaining works. All of this is to say we had many owners who weren’t coming to the bargaining table with the right attitude.

Initially, very few union members were involved in the negotiation. We have a small group of active members who took an interest, but they’re a tiny percentage of the 1,200 workers. I would sometimes speak to long-time members who had no idea the negotiation was going on.

Over 99.7% of workers at SFO voted to strike. How do you account for this huge show of support?

Many people I spoke with had no idea how the strike vote process works. I had to explain to many people everything that had to happen and why we were striking. It took patience and hard work from organizers and Local 2 staff.

A big part of the reason for that is people at the airport were working two or three jobs, commuting for hours both ways, and mainly focused on survival. They didn’t have the time to engage in the way I had. Others felt they were neutral on the situation, and we needed lengthy conversations about what “neutrality” means during a disagreement between union members and their boss.

People think the union is a service like your cable provider. But that isn’t how it is. You pay your dues, sure, but you also get out what you put in because you and I are the union. It’s like a car. You buy the car, you gas it up. But you’re the one that has to push the pedals and turn the wheel. That metaphor really helped people understand.

The activists within the union were phenomenal about getting people engaged. They got me involved early on, and I found them so interesting to learn from. When you talk to someone who’s been in 40 strikes, you want to hear about what that is like. There was a ton of work put in by Local 2 members and staff, and the strike vote number is a clear indication of how well they did.

The organizers at the union were rockstars — they’ve been so critical at every level of this effort, interacting with uncooperative owners, getting people to come to meetings, and so on. That enthusiasm fires up active members like me and encourages us to get engaged.

There are language barriers. Some people speak Tagalog or Spanish, so we had to make sure everyone was listening in the language they were most comfortable with. Soon, everyone was engaged and enthusiastic. We were all signing on to come to meetings, showing up for votes, and getting engaged.

Part of our job as leaders in our workplaces is to dispel fear. We need to help our coworkers understand that the strike isn’t a secret or something we do to “attack” our boss. It’s about us getting what we need and having our demands met. Getting people to believe in their collective power is tough! That fear is so strong and people need constant assurance that if they stick together they can win.

I remember people calling me with concerns, asking me how long the strike could go on, asking what would happen, and all you can do is explain things as clearly as possible and assure them we will win if we stick together.

Describe the strike itself. Was it your first strike? What did it feel like? Did you feel the public was supportive?

I’ve been through one other strike that I was not really involved in. I was supportive of it but I spent the time at home with my two-month old baby, so I didn’t scab but I also didn’t picket.

It was an incredibly diverse range of energies and feelings, ranging from deep fear to exhilaration — the whole experience was intense! I was trained as a picket captain, but it’s different once you get out on the line.

The airport, security, and police were fair to us, and people drove by and honked in support. Most passengers were really supportive. I’m sure not all of them, but overall it was very positive.

We coordinated with the flight attendants, who had their own action planned. Even now, when I see attendants in the airport, we acknowledge each other, which is great! You can see that connection being built not just within our local but with other unions as well.

I had to learn chants on the bullhorn on the fly. I tried really hard to be as enthusiastic as possible, because ultimately our job is to be disruptive and get noticed. It’s a show of strength but also something meant to agitate and annoy for awareness. It’s about getting people to care. Even our strike vote didn’t get the owners to care, so we needed to get louder, more active, and make it so we couldn’t be ignored.

We sent a delegation down to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors meeting when we knew airport officials were going to be reporting to the board and told the supervisors we had authorized a strike. That changed our engagement with the airport officials.

Supervisor Rafael Mandelman came out to the airport and joined us on the picket line. So politicians were helpful. The board was supportive of us and called on the director of SFO to solve this issue at a special meeting.

What are the key points of what you won? Can you explain why the retention policy is important?

It was a huge victory. We got a great contract and I actually think we got a stronger one than if we had just gone through negotiations normally, which I hope is something workers take note of. We weren’t asking for anything crazy — we wanted people to keep wages at a sustainable level and have good healthcare benefits.

The retention rules relate to the bosses’ restrictions in hiring. A common thing they try to do is to change or buy an old place and kick out the former staff who have been working there for years. But we said no. You have to reward people for their hard work. You also can’t bring in, say, your nephew, as an example, and give them the best shifts. You have to hire workers according to the union seniority rules. Also, all of the hiring is now going through our hiring hall, which is important, because rather than forcing us to seek out seniority rules violations and solve them, they just won’t happen.

The average household income in the Bay Area is over $130,000/year, which is almost four times the amount someone would make working full time at $17.05 an hour. Why do you think you had to strike to get a raise? What made the owners unwilling to negotiate in good faith?

Our lawyers estimated that our strike cost the owners $250,000 a day. Put that in context of what we were asking for. If that’s how much they make in a day, they can afford to meet our demands. It seems so simple, right?

I think it was the new businesses. Many owners don’t seem to understand the rules or understand how negotiations usually work. I also personally believe that there’s a bit of a “pandemic hangover”; workers AND owners in the US are talking about how much the pandemic upset things. Bosses feel emboldened to get away with more because there’s public sympathy for small business owners, but our strike showed that the sympathy is with working people.

We have to understand we have power, and our cause is righteous. Our jobs are important to a place like San Francisco which depends on tourism.

There’s been a recent upsurge in labor organizing among service workers, particularly at chain restaurants like Chipotle and Starbucks. As a union service worker, what’s your view on why this is happening now?

I think it’s because the wealth gap is getting larger and workers are getting more desperate. I look at it in the reverse sometimes, and I’m shocked that people aren’t more active when unions are clearly so beneficial. I think that’s a sign of the system we live under and the fear we are taught to have of unions. Growing up, I heard of negative talk towards unions, and I still sometimes deal with it with coworkers who are union members! We’ve all been taught that trickle-down economics really works and it’s better for everyone if the bosses run the show.

I’m hopeful that every victory, whether it’s us or at Amazon or Starbucks, changes this. It’s staggering that those places, where workers are the most abused, aren’t already unionized. It shows the power of anti-union efforts and ideology.

If you line up the things the union brings you — job security, better working conditions, paid vacations, a pension, a raise, seniority — no worker doesn’t want these things. And yet you still have this fear. People are always looking over their shoulder at their boss.

What would you say to workers at a restaurant, coffee shop or bar looking to organize?

I’m so new to this but one of the beliefs I have is you have to trust your feelings and instincts and have faith in yourself in each other. You can build confidence being around other people who are helping you organize. That’s how you overcome that fear.

Walking the picket line and helping with the strike was an honor, and I was in awe of the workers who struck with me and the organizers who were there with us.

I know organizing seems super scary at first. But once you win, the bosses will change their tune and figure out how things need to go. It’s never as big a deal as they make it.

We need to learn to help each other in other ways too! That’s what unions are about, and we need more of that. We also need it between unions, even if it’s just trading stories or tips or showing up at picket lines for each other.

Believe you are right, you have a right to demand a life of dignity in exchange for your work. Your agreement with your boss is that you help them make money, and you should be able to expect dignity in return.

Disclaimer: The content of this article and interview is based on one person’s experience and does not necessarily reflect the views of UNITE HERE Local 2 or its members.

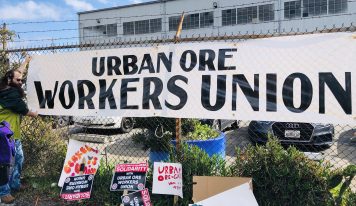

Photo from Unite Here Local 2’s Twitter page